More Than Spinning Wheels

by Erin Hassett

Covered in dust, sweat, and bicycle chain grease, we finished the second day of our bike tour at an unexpected desert oasis somewhere in California along the Mexico border. Dismounting our metal steeds, Casey and I wheeled our way into Narnia. Hammocks hung in the sparse trees, and peacocks strutted in between dogs and chickens. Among stringed lights, a drum circle was slowly beating to a rhythm, a welcome that was surely just for us. Nearby, a labyrinth of giant sandstone faces and creatures more than a hundred years old wove its way along the periphery of this unusual desert campground, and we got lost roaming through the sculptures until we scrambled to the tallest boulder and sat overlooking the dry and expansive valley. As the final pastel lights of dusk melted away, we claimed a free-for-cyclists campsite, built a campfire, and exchanged stories with other riders who were also traveling across the country. But unlike the other cyclists who escaped into their tents at night, we cowboy camped directly on the dirt ground with nothing between our earthly human bodies and the galaxies in the sky.

In 2022, I was new to bike touring. I plunged into the activity like it was a life raft that was going to save me from my career path. The trajectory of the next five years of my Ph.D. program was laid out for me on paper: I would no longer be out in nature collecting ticks and doing small mammal trapping for an ecological study on tick-borne pathogens. Rather, I was going to be in a sterile lab with sterile pipettes and sterile gloves under grating, fake lighting injecting mice with viruses to see what would happen to their brains. I didn’t want to kill these mice and cut their heads off. I needed out. More specifically, I needed to be back outside where I belonged.

My solution was to get on a bicycle and go somewhere else, anywhere else. With my escape planned in March 2022 to coincide with spring break, I dug through the internet and discovered the Southern Tier Route: a San Diego, CA to St. Augustine, FL route that promised warmth and novel landscapes for me. Not wanting to travel solo, I reached out to the only other person who could possibly be interested in doing something wild and last minute like this: Casey Hale. She and I graduated from the same entomology department, and, at the time, she was bouncing around out West, living out of her van, rock climbing, and working at a ski resort. Of course, she said yes.

Casey Hale and me at the desert tower. California, 2022.

With the initial shock of a lady cyclist and her female friend biking alone, most people––friends, family, strangers on the road–– just ended up asking us “But…why?” As in, why travel by bicycle? Why not by car?

It’s true, if you’re having a crisis and seeking new vistas, you can see more by car than you would by bike in the same amount of time. By car, you can even selectively destination hop to skip past any landscape monotony to maximize seeing tourist attractions. Another perk is that you get the luxury of not having to exert any effort at all; a truly relaxing vacation to feel rested and rejuvenated (while you get your life back on track).

I have sat, quite literally, with this question of why often, mostly while I am seated on my bicycle. This question appears most frequently during times of discomfort, of uncertainty. It comes when my legs are exhausted, when the only visible sight in the distance is a tumbleweed, and when I have yet another cold-soaked container of ramen waiting for me to eat for the 6th night in a row.

Getting myself into these situations wasn’t entirely out of the blue, though. After all, I was active in cycling communities, and I knew that bike touring existed––I had seen the bags that strap to bike racks for hauling gear, and some of my closest acquaintances had regaled me with tales of bicycle travel. Not to mention, I was aware of the litany of personal, environmental, and profitable benefits from biking: improved cardiovascular health, lower carbon emissions, and economic boons to the small towns cyclists pass through (rather than drive past), just to name a few.

What I hadn’t planned for, however, were the unexpected and fortuitous moments that occur while bicycle touring that are forever life enriching, and these moments of connection and community make the grueling adventure worthwhile.

Deeper Human Connection

It has become apparent to me that, when you are traveling by bicycle, you are a mobile anomaly, particularly in the U.S where cycling infrastructure leaves a lot to be desired. But whether in the U.S. or other countries in the world, you are still a vulnerable human on a bicycle with a story to tell and an unknown destination (to others), and that attracts onlookers.

After professionally fine-tuning our responses to “Where are you going? Where are you coming from?”, Casey and I were sometimes rewarded with invitations. A fireman chief offered us his living room when all the spare beds at the fire station were occupied. A pastor in Louisiana opened his church for us to sleep in where we enjoyed some rare AC and a generously provided morning breakfast. In Alabama, a fleet of speedy cyclists on expensive bikes surrounded us to make conversation, and then they treated us to a hotel room and dinner.

As my husband Uriel Menalled, another bike enthusiast, puts it, “A car gives you a physical barrier to the outside world, and you’re moving through foreign landscapes in your little bubble. On your bike, you’re really exposed. Humans can’t not care about another human who’s in an exposed position, and so people approach you and ask questions, or you have these random conversations because you’re in the middle of nowhere.”

In summer 2023, Uriel completed a 60-day cycling tour from the Mediterranean Sea in southern France to the Arctic Circle in Norway. Traveling across many countries with multiple languages and cultures, he met countless strangers, each person sharing about their own lives and ways of living. These random interactions can lead to something magical and memorable, often being the interaction that keeps you from giving up.

Uriel biking in Norway with another cyclist, Gerry, whom he met on tour. August 2023.

Uriel reminisced about one of his favorite moments on tour. “At the beginning, I was alone, and I really struggled with that. I went to a host’s house after being isolated for a while. He lived in this beautiful village, and you could see the Alps and the Jura mountains. When I arrived, he asked if I wanted to sing some American songs. I had this cathartic release…we started belting out Country Roads, Leonard Cohen, and Bob Dylan. It was nice to go from being alone in my own head to being with these people singing––something I don’t do. It was an intimate and personal thing. You’re so vulnerable when you’re touring that people want to open up to you, and you want to open up to them too.”

A little closer to home, my friend, Ben Grodner, shared a similar uplifting experience that occurred to him in Wyoming. He and his girlfriend, Megan Guinn, were touring across the U.S. through the beautiful and vast countryside of the Great Divide Basin in the Wind River Range. Megan developed a disconcerting knee pain, and they were struggling to finish riding that day when a truck driver hauling a sheep trailer slowed down to check in. After seeing their struggle, he had Ben and Megan load their bikes into the back of his truck, and he drove them to his farm where they slept that night in the sheep trailer. That evening, he bought them dinner, and they passed the time learning about each other and his life as a sheep farmer in this town.

“It was a crazy interaction with someone who we never would have met,” Ben explained, still in disbelief. “Never would we have had this interaction, learned all about the place, or have appreciated the kindness in the same way. When we rode to the next town to a physical therapy place, the lady checked out Megan’s knee and fixed her up. At no cost!”

Ben sitting next to the sheep trailer where they slept the night of their truck rescue. Great Divide Basin, WY. July 2018.

In my own experience, I owe the success of my travels to the kindness of strangers. When Casey and I ran out of water in the desert, a man in an RV didn’t hesitate to refill our bottles. After a particularly brutal day in California without shade and with five flat tires, a couple at a campground made us tacos, gifted us muscle salve, and drove us to the grocery store–– a luxury when another ten minutes on the saddle would have meant physical and emotional agony. In Arizona, after failing to secure a place to sleep, a sweet man allowed us to camp in his yard while his mother brought us her own homemade canned peaches. These serendipitous interactions could never have been planned for in advance, and they are what make cycle tourism possible, both for the physical assistance and for the unexpected generosity that boosts your morale when you need it the most.

Providing the support and comfort for weary travelers also has its own rewards. Zoom in to Upstate New York: Anne and Carl Wick are avid cyclists who, in their retirement, settled onto and started a small farm. They have cycled thousands of miles in the U.S., sometimes on a tandem bicycle, and have welcomed many cyclists from multiple countries into their home, including Uriel and I one weekend in November. They, like us, have their home listed on a cycling app which offers shelter and services to other bike riders on their journeys. After digitally connecting with Anne and Carl, we escaped the sedentary work week to ride part of the Erie Canal which led us to their cozy farmhouse. Though decades separated us, we bonded over shared environmental interests, and I was a sponge to everything they were willing to tell me about their lives.

“Our young visitors particularly help us stay in touch with the next generation,” Anne explained. “They open us to new ideas, entice us to explore new places, and help us puzzle out why we feel such a strong connection to strangers who just happen to share our passion for cycling and touring.”

A New Way of Living

Being exposed to new areas, cultures, and people have benefits that will remain with you for the rest of your life: it enhances your cultural awareness and gives you a stronger respect for diversity, leading you to be more empathetic and tolerant to mixed perspectives (1). It also fundamentally improves your critical thinking and problem-solving skills by allowing you to examine issues from multiple points of view (2) . By talking to strangers and letting them tell you their story, you will gain far more than you ever hoped to receive, perhaps being convinced to make changes in your own life.

When I think about the people who made a lasting mark on me, I am mentally transported to a tiny town in New Mexico, just over the Rocky Mountains. Hillsboro (pop. 199) is the kind of no-cell service town that you bike past in under a minute that has a few pastel-colored store fronts, some that might be open.

After hauling it over the Rocky Mountains, Casey and I were excited to stop for the night and sleep in the public park. We quietly settled in, and slowly, the locals coalesced. It became clear that this park was the happening place for socializing: beer passed around all night, and, for a brief moment, we became witnesses to each other’s lives. Of all the people we met that day, it was Parker that stood out most. He was a flannel-wearing, tangled hair, 30-year-old nomad who had been on the road since he was 19 but who periodically set up residence in Hillsboro. He owned very little and had no social media, but his relationships were incredibly rich, and he had a carefree outlook on life. In under 24 hours, I was inspired to live more gently, simply, deeply.

Casey, Parker, and I in the public park. Hillsboro, New Mexico, April 2022.

The following day, Casey and I delayed our exit until after noon to not miss the tiny farmer’s market and “Picker’s Circle”, a gathering of local musicians who played Americana and Bluegrass music, including Parker who sang a song titled “Cruel Winds of Oklahoma”. As we sorrowfully mounted our bikes to leave, Parker reminded us that our trip is about the journey not the destination. This saying meant more to me in this moment than it ever had previously, my time in Hillsboro emphasizing that reaching a physical landmark destination on a map could never stack up to the experiences of connecting with and learning from strangers.

Anne and Carl, the retired farmers in New York, have also been inspirational by showing me what life is like when you intentionally think about the health of your food and land. After a morning cup of coffee before mounting the bikes to return home, Uriel and I followed Anne to the barn where we joined in her routine animal chores: feeding the chickens, ducks, and geese. Metal buckets were filled with a homemade mixture of seed and grain, selected with care for each flock. She indicated to certain birds, calling them out by name and telling us their backstory including any noteworthy personality traits. We then toured her large garden where she showcased her botanical masterpiece and described each plant’s edible or medicinal values. Everything in her garden had a purpose. Everything was cultivated with care.

“Hosting [other cyclists] has provided enriching experiences, both for us as hosts and for our visitors,” Anne explained. “Visitors get to see radically different ways of living. Perhaps for the first time, they see what it looks like and what is involved with being intentional about your food and environment.”

On the ride home from their farm, I pondered all the ways I could be more intentional in my life–– to know and appreciate where my food was sourced from and what sustainable changes I could make in my kitchen. They have invited us to return in the future to learn more about permaculture on their farm, and we can’t wait to take them up on that offer.

A Deeper Form of Tourism

Tourism by car lends itself to destination hopping which can be very rewarding in terms of maximizing the number of photo-worthy sites you see, but, in many respects, it is quite shallow. The unique aspect of bicycle travel is that it fills in the blanks between tourist attractions, showing you a vastly under appreciated world where wonderful life and landscape exists. When you travel slowly between these sites, you acquire a deeper understanding of a place in its entirety and are often rewarded with hidden gems that are a secret to the rest of the world.

“Traveling by bike is the optimal way to do tourism,” Uriel confirms. “You move at a speed that’s fast enough to go into different landscapes and towns in the same day, but you’re slow enough where you are exposed to and immersed in everything in between. You cross the threshold from being a tourist to being someone who is trying to understand the experience and culture, and that exposure puts you in a position where you can have genuine and rich interactions that you couldn’t have if you were in a car going from tourist destination to tourist destination.”

My frequent cycling companion across the glacial hills of the Finger Lakes region of New York, Sondra Wayman, echoes the sentiment: “To move yourself around the landscape, to participate in the contours of the land in that place. You feel each hill and each descent. The name of a distant place that you inch towards each day eventually becomes your destination.”

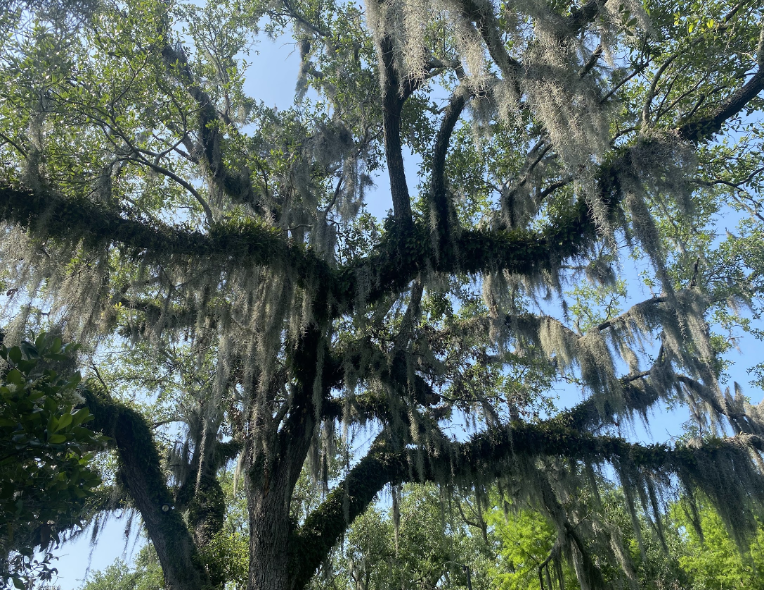

In rolling with the contours, you are privy to experiences that you wouldn’t have at 70 mph in a metal box, including exposure to the richness of the flora, fauna, and physical beauty at finer scales. I’ve enjoyed rays of sunrise shining through the needles of cacti species I’ve never seen before, reached out to feel the wiry tangles of Spanish moss draping magnificently from trees in New Orleans. I have raced alongside tumbleweeds in Texas and cruised past fields of flowers growing as wildly and as free as I felt cycling next to them.

Sunrise through the cacti, CA. March 2022.

Spanish moss in Louisiana, 2022.

The Challenge, The Reward

There is no denying that using your body to propel forward for multiple days and weeks can take its physical toll; however, there is an irrefutable gratification and sense of triumph you receive that wouldn’t occur if traveling by a motorized vehicle. Whether it’s reaching the top of a mountain, dismounting at the finish line, or just kicking your feet up at the end of a long day, there is a deep satisfaction in covering distance with your own hard-working muscles. We may have dopamine to thank for that. Not only is there a surge of pleasure from completing something big, but we get a rush of dopamine from seeking the reward as well (3). Having a hot, calorie-laden meal waiting at the end of a long ride, chasing that endpoint, yearning for that vista–– we are wired to want it, to chase it, to achieve it.

There is also the transformative experience of leaving your comfort zone and realizing that you are far more capable than you had previously known. In the moment, it is tough and uncomfortable, but putting yourself into the ‘groan zone’ leads to immense growth and learning (4). When you stretch to or beyond your limits of comfort, it is also likely that you will boost the satisfaction in your life (5) , even giving you greater confidence and comfort when you are in future unpredictable circumstances (6).

For Casey and me, we spent 53 days biking across the United States. In those 53 days, we battled intense heat in Texas–– the kind that makes your own handlebars too hot to touch and forces you to hold your breath while you pass bloated and rotting carcasses on the roadside every mile. We fought saddle sores, rashes, sunburn, and bloody collisions. We became just another vulnerable organism in an ecosystem of coyotes, wild burros, and mosquitoes, subject to unsympathetic lightning storms, headwinds, and Floridian drivers. Even with a strong will, our human bodies revealed their weaknesses: halfway through the tour, I lost all dexterity in my hands, being unable to squeeze my shifter or even unbuckle my own panniers. Casey’s excruciating neck and jaw pain had us ramping up our mileage to expedite the grand finish.

In all the struggles we faced, we persevered. On a sunny Saturday afternoon in May, our wheels sank into sand, and Casey and I plunged fully dressed into the Atlantic Ocean.

Casey and me at the Atlantic Ocean after biking across the United States. St. Augustine, FL 2022.

Why?

So, why do I travel by bicycle?

The actual answer to this question appears in many ways and, often, unexpectedly. It comes in the form of a healthier life for yourself and the planet, a home cooked dinner and good conversation with strangers, free pancake breakfasts at the KOA, astonishing landscapes, the rewarding sense of accomplishment, new friends who leave their mark on your journey, small one-shop towns that take up permanent residence in your mind and heart, and different insights into the way life should be lived.

“Bike packing has made me more optimistic about humanity,” Uriel concludes. “The world is net good, and that’s something you realize when you bike.”

~

Erin Hassett is a journalist with a passion for environmental and recreation writing, highlighting women in the sciences and in the outdoors, through her blog This Footprint. She is a PhD student at the SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry, and her own research focuses on wetland greenhouse gas cycling. In her spare time, she can be found reading a book, backpacking up a mountain, or traveling on two wheels.

Featured image: The author’s bicycle on tour. Malans, Switzerland 2023.

Author’s note: “More than Spinning Wheels” is an article designed to encourage readers to embark on an adventure through a new form of travel, inspired by the author’s own cross country bicycle trip. Travel, at its core, is a transformative activity–– by traveling to new places and being exposed to different people and ways of living, we can be inspired to live and think in novel ways. However, bicycle travel offers more: an opportunity to understand what happens in between touristic destinations. There is a plethora of life and beauty outside the confines of motor vehicles, particularly outside of landmark locations which predominately attract tourists passing by. Furthermore, the richest interactions occur when people allow themselves to become more vulnerable–– to the environment, to strangers, and to kismet happenstances. With accounts from others of various ages and backgrounds, this feature with emphasize how bicycle travel can irreparably change a person for the best. Read at your own risk.

~

References

1. Naz, F. L., Afzal, A. & Khan, M. H. N. Challenges and Benefits of Multicultural Education for Promoting Equality in Diverse Classrooms. Journal of Social Sciences Review 3, 511–522 (2023).

2. Aziz, M. An Empirical study of Entrepreneurial Intent; An application on Business Graduates of Sultanate of Oman. Science International (2019).

3. Bromberg-Martin, E. S., Matsumoto, M. & Hikosaka, O. Dopamine in motivational control: rewarding, aversive, and alerting. Neuron 68, 815–834 (2010).

4. Luckner, J. L. & Nadler, R. S. Processing the Experience: Strategies To Enhance and Generalize Learning. Second Edition. (Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company, 4050 Westmark Drive, Dubuque, IA 52002 ($36, 1997).

5. Russo-Netzer, P. & Cohen, G. L. ‘If you’re uncomfortable, go outside your comfort zone’: A novel behavioral ‘stretch’ intervention supports the well-being of unhappy people. The Journal of Positive Psychology 18, 394–410 (2023).

6. Cohen, G. L. & Sherman, D. K. The Psychology of Change: Self-Affirmation and Social Psychological Intervention. Annual Review of Psychology 65, 333–371 (2014).